When I was in high school, I was fascinated by geography, and it struck me that there was a highway that I could hop on in my car and drive all the way down into South America. As an imaginative young girl growing up on the Texas-Mexico border, the idea of a road that could take me from my sleepy border town, Laredo, Texas, to the edge of the world in South America, left me awe struck. In high school I learned that this highway is called the Pan-American Highway. According to Britannica.com, it is approximately 19,000 miles in length and begins in Alaska, makes its way into Canada, the U.S., then into Mexico, through Central America and finally to the tip of South America, except for the approximate 55 miles in length and 30 miles wide along the Panamanian-Colombian border. This stretch of land is called the Darien Pass.

The Darien Pass, or Darien Gap, is not a forgiving stretch of land. In photos, the terrain looks lush, tropical, green, and untouched. This stretch of land is a geophysical break in the Pan American Highway, as it is undeveloped, but beyond this appearance, temperatures rise to 95°F, with high humidity, it has dense rainforest, jungle, muddy swamps, and dangerous animals. The terrain is unforgiving, yet today, thousands of people, mostly Venezuelans make their way through it to begin their journey to the U.S. On this path, people are injured because of the elements, raped by other travelers, many succumb to the muddy hillsides and paths, and many die, or are left behind. No one is spared, not the children on their parent’s backs or the elderly struggling to keep up. It is a trek for the survival of the fittest and for the lucky ones.

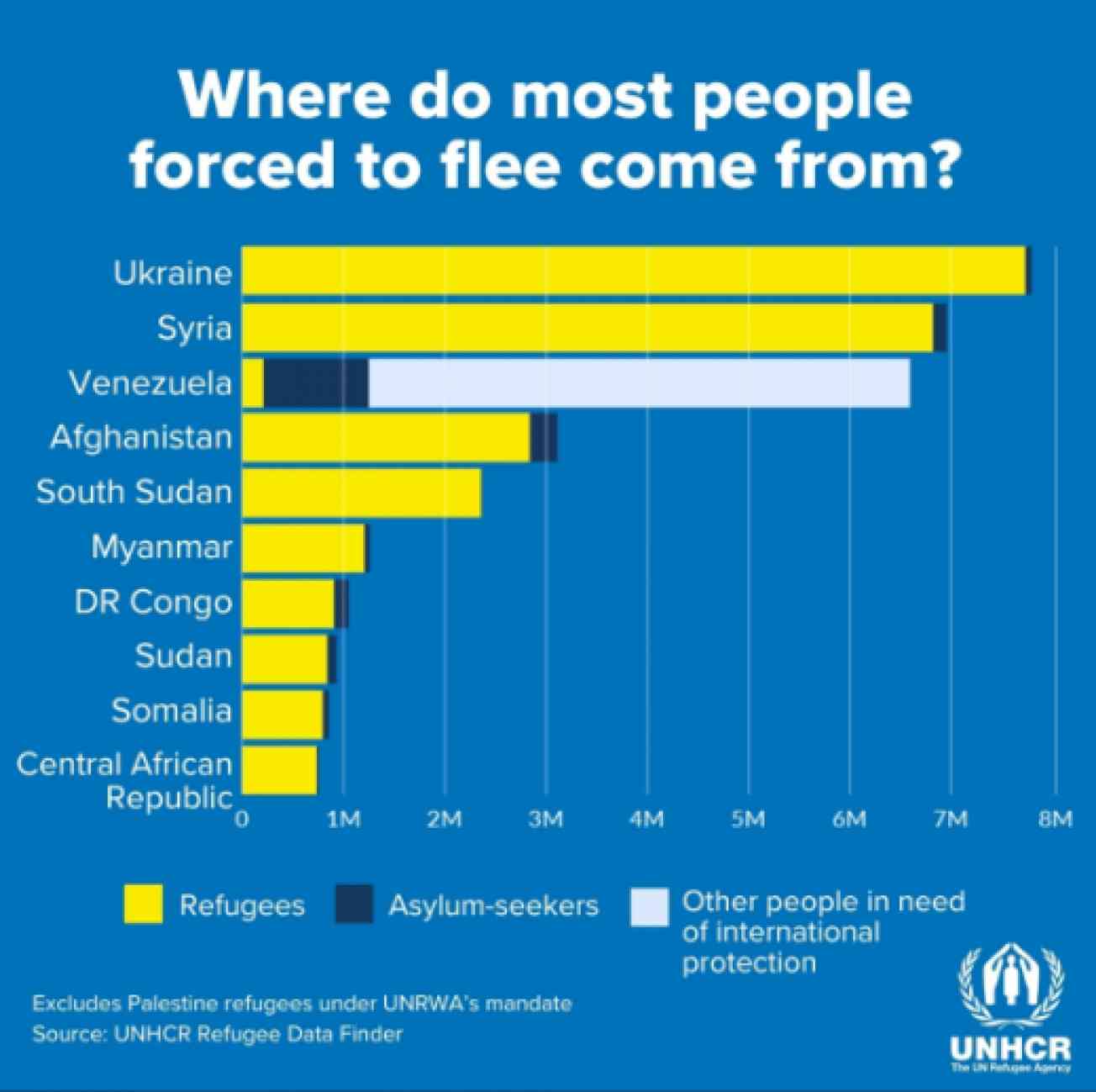

A recent New York Times article, “In Record Numbers, Venezuelans Risk a Deadly Trek to Reach the U.S. Border,” includes photos of people on this journey. The photos are raw, and some are hard to look at because they show the hard expressions of survival on the faces of the people on this dangerous journey. As I look through the photos, I scan around looking for familiar faces. Faces that I might have seen on the streets or parks in Bogota, where I live now. In Bogota, my friend and I run a volunteer outreach group, and since its inception, we have met hundreds of refugees, mostly Venezuelans. They are refugees, some are fleeing violence and oppression, but many are fleeing economic hardship. Friends back home in the States ask me why the Venezuelans are fleeing in large numbers to the U.S./Mexico border. It is a question that I ask myself too. My experience with the Venezuelan refugee and immigrant community is that they are exchanging one desperate living situation in Venezuela, with another in Colombia, then another one along the journey to the U.S/Mexico border, where their fate is uncertain.

The risk for people making this journey is worth it considering their current situation in countries like Venezuela. There are people from other countries making the journey as well, including people from Haiti and Africa. They do not have very much to lose, so they decide to embark on this journey where at least in a few months, their fate might be improved as refugees in the U.S. In host countries, like Colombia, many feel like they have limited options for themselves, and their children, and they believe that the U.S. has much more to offer them. According to the article, there were “just below 11,000 people” crossing annually between 2010-2020. In 2022, thus far, “more than 156,000 people have crossed, most of them Venezuelan.”

An example of someone considering making this journey is my Venezuelan nail technician who dreams of life in the U.S. for her and her son. Many of her relatives have already made it to the U.S. via flights into Mexico, boat rides to Central America, and of course through the Darien Pass. Making that journey through the Pass terrifies her because of stories that her relatives have shared with her about the horrors that they have witnessed along the Pass. But her relatives’ stories in the U.S., along with the promise of a secure job and safe living conditions, appeal to her. Despite the danger, she still dreams of making it to the states because of the life she dreams of for her son. Here in Colombia, she has a job, she has documents, and her son is enrolled at a colegio (school), but she still feels that her future would be better in the U.S. Every two weeks I go for a manicure with her, and I can sense her inching along towards her resolve to make her American Dream come true. The belief that the U.S. has opened its border to Venezuelans has driven thousands to make that journey to the border, despite warnings from U.S. officials that the border is closed.

The border may be declared “closed” by American officials, but the American Dream is not dead, and if people continue to face desperate situations in their home countries, they will continue to make desperate choices and risk everything to make it there. Now as an adult living in Colombia, I never could have imagined that big–that I would be living on the continent that marks the end point of the Pan American Highway.

Despite that break in the Highway, the Darien Pass is not a deterrent to people seeking a better life, it is simply the first of many obstacles on the road to the American Dream.

According to the UNHCR June 2022 statistics, Colombia is host to over 1.8 million Venezuelans and nearly 7 million internally displaced Colombians.

Click the link below to learn more about the Venezuelan/Colombian situation and how you can help:

Venezuelans in ColombiaOfficial Statement on the Detention of Refugees and Ongoing Community Violence

With another death in Minnesota and continued violence toward individuals and groups standing up for their communities, we acknowledge the profound fear and uncertainty people are feeling--not just locally, but across the country.

On top of this, there are reports that refugees invited and admitted to our country through the U.S. Refugee Admission Program are now being detained, meaning that our new friends and neighbors feel that fear most acutely.

Refugees have already fled violence and persecution once. They came here legally, seeking safety. In moments like these, we reaffirm our commitment to building communities where refugees and immigrants can live without fear. Where they can go to work, send their children to school, and build lives of dignity and belonging.

We call for due process, accountability, and humanity in all immigration enforcement operations. We call upon our leaders to demand the demilitarization of our neighborhoods and cities. And we call on all of us to continue the work of welcoming and protecting those who have been forcibly displaced from their homes.