International Medical Graduates: A Case for Capturing Skilled Immigrant Labor

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan reminded Americans that “our immigrant heritage and our capacity to welcome those from other lands” are among our core strengths. Following an influx of displaced Cubans arriving in Florida, he outlined eight guiding principles “designed to preserve [America’s] tradition of accepting foreigners to our shores…in a controlled and orderly fashion.”1 While welcoming those who have been forcibly displaced remains an American ethic in varying degrees, now is a critical moment when America must also value immigration as a dynamic workforce resource.

Despite frequent calls to preserve American jobs, we face a multi-faceted workforce crisis that will only worsen over the coming decade. Traditionally immigrant laborers have primarily filled low-skilled labor needs, but today’s forecasted gaps include high-skilled industries like healthcare at a scale that cannot be filled by American-born workers alone. These gaps will grow to a shortfall of roughly 6 million open positions before the end of the decade. Multiple factors have contributed to our current condition, including post-pandemic job market shifts and a current mismatch in skills versus demand, but of greatest consequence is the fact that “as Baby Boomers exit the workforce in large numbers and become consumers of services,” unprecedented efficiency and deliberate, data-driven solutions will be required to keep up with massive workforce shortfalls.2 In fact, forecasters anticipate that from 2024 to 2032, U.S. population growth will outpace labor force growth by nearly 8 to 1.3 Consequently, innovative immigration policies and workforce development practices must be baked into any designed path forward.4

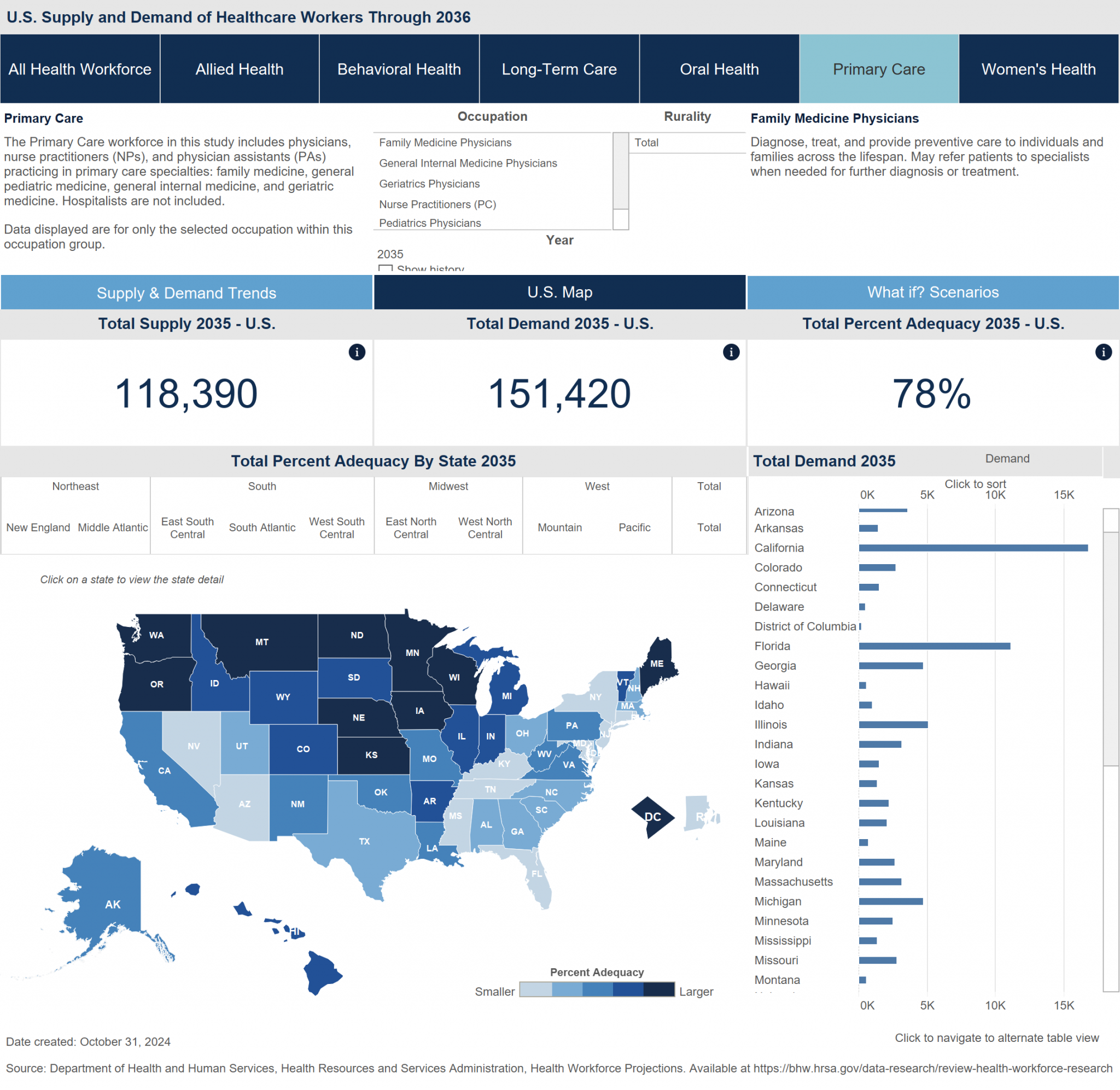

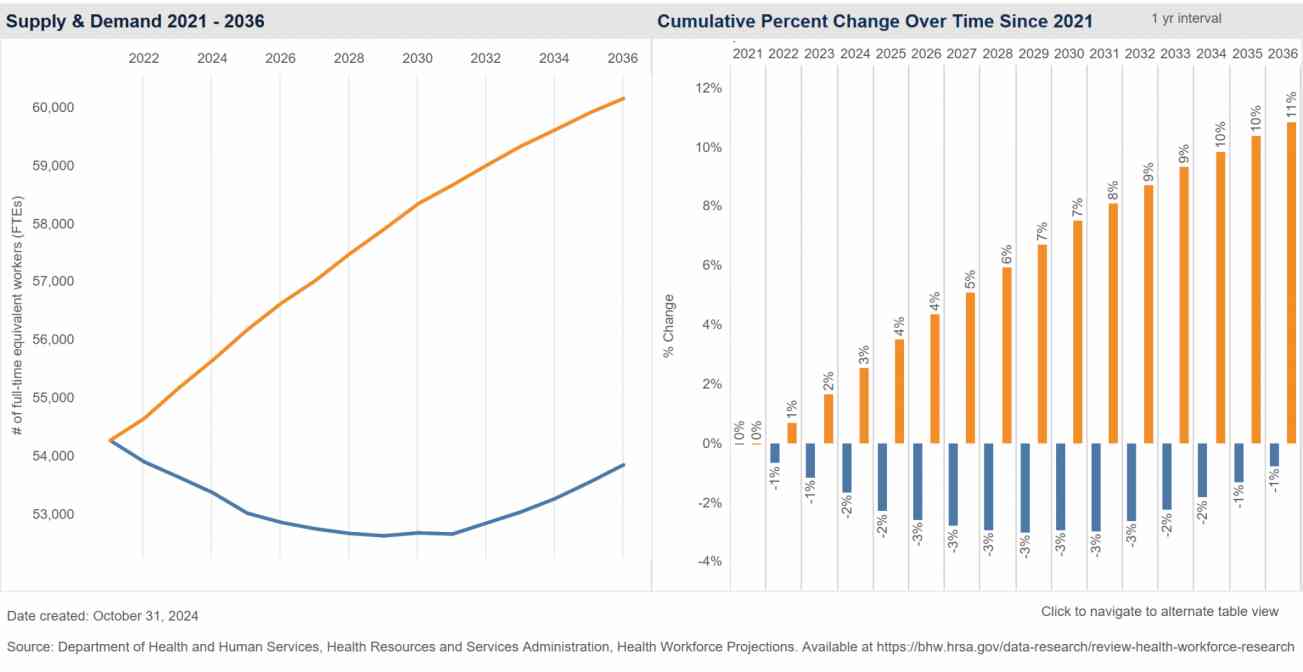

One only need look at the healthcare labor sector to understand the impact of the labor shortage. “A well-trained, culturally competent physician workforce is vital for keeping Americans healthy. Since it can take over a decade of education and residency to prepare a physician,” the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. advises that “the United States should take steps now to address future physician shortages.” They predict the following shortages over the next 15 years, with the largest shortages forecasted in non-metro areas:

Nursing = 437,040 including:

o 337,970 registered nurses (RNs)

o 99,070 licensed practical nurses (LPNs)

Physicians = 139,940 including

o 68,020 primary care physicians

o 7,800 cardiology physicians

o 6,610 Ob-Gyns

o 6,300 anesthesiology physicians

o 4,360 nephrology physicians“5

Shortages of this magnitude impact both patient waiting times as well as strain an already overtaxed health workforce. Consequently, healthcare gaps are most acutely felt in rural communities, where 15% of Americans reside but are served by only 10% of practicing doctors.6

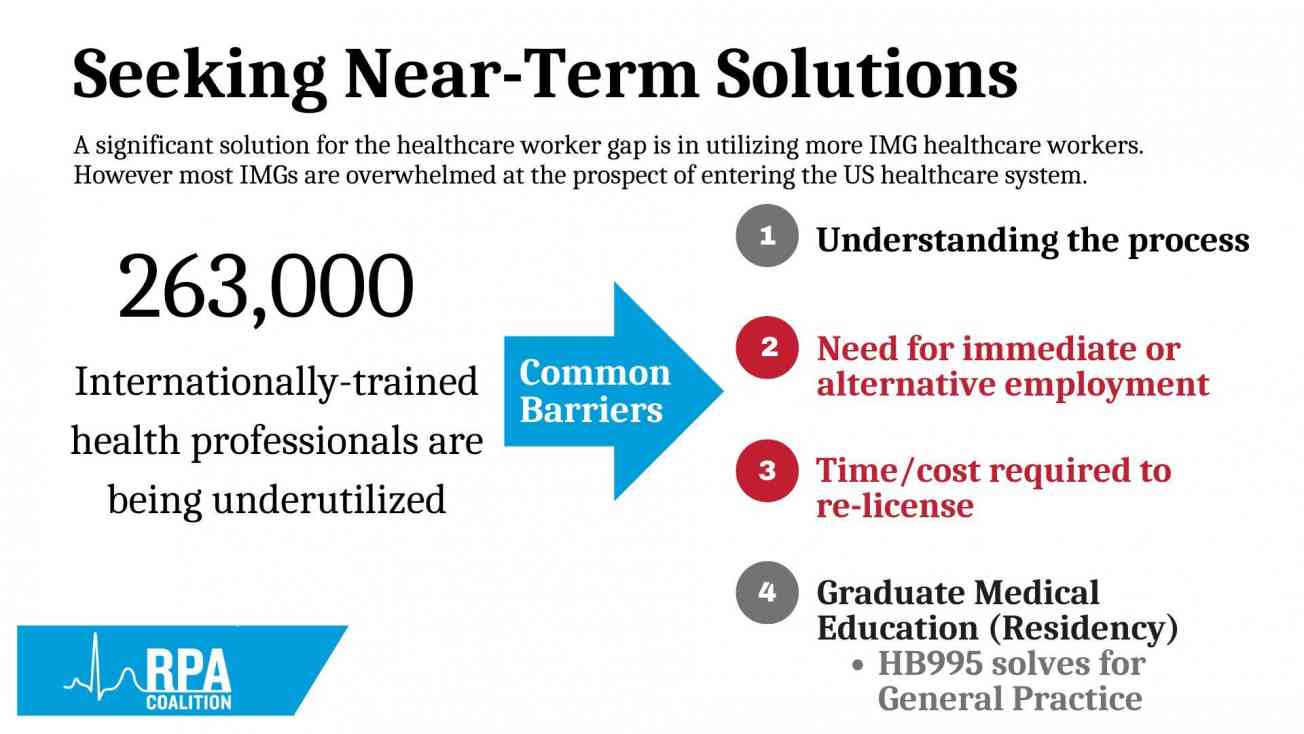

One solution to help fill this healthcare workforce gap is to strategically integrate foreign-trained physicians. Already “nearly 2.8 million—or 18%—of the healthcare workers in the US have come from outside the country. Foreign-born workers account for one in every four doctors, one in five registered nurses, and one in four health aides…[and] make up such a large share of the US workforce that it could not function without them.“7 Still, the Migration Policy Institute estimates that 263,000 non-US IMG health professionals [within the United States] are enduring what is sometimes referred to as brain waste. These include doctors, nurses, and therapists, many of whom are multilingual, and almost all are legally present.8

International physicians without H-1B visas, including refugee physicians who resettle in the United States, experience significant barriers to re-entering the U.S. healthcare workforce that postpone, limit, or completely hinder their ability to find work in any healthcare capacity. Primary among these challenges are 1) the time and financial burden to study and pass the United States Medical Licensure Examination (USMLE), estimated to take more than four years and more than $6,000 plus lost wages; 2) a requirement to re-do multi-year U.S. residency against steep competition at minimal pay; and 3) for some, insufficient English fluency. These barriers limit an international doctor’s career potential and represent a missed opportunity where thousands of skilled international physicians trained in internal medicine, obstetrics, public health, pediatrics, emergency medicine, surgery, and other fields must find work outside of healthcare.

One 2023 qualitative study found that despite the challenges, displaced international physicians’ passion for patient care remains high. One refugee doctor explained, “I really want to continue to work in the medical field. At first people were saying, ‘Why don’t you work at Marshalls? Why not work at Amazon?’ I said that I do not want to work somewhere where I do not use my training. I didn’t study for more than two decades to not work in my field.” Another said, “For two years I haven’t [treated] a patient… Every day I feel like my medical skill is dying.“9

To more easily capture the skills of international physicians, some employers and policy makers are developing streamlined approaches to lowering the barriers. So far eleven states have passed legislation enacting a provisional licensure pathway that replaces the need for experienced international physicians to repeat residency, and at least fifteen others are considering similar bills.10 In other places, institutions like UCLA’s IMG Program provide stipends to offset the costs for retraining11 and similar innovations can be found at the University of Minnesota.12 In Colorado, support from private-public partnerships is funding the Spring Institute for Intercultural Learning13 as an innovative solution to shorten re-licensure pathways for international physicians.

More large-scale private-public investment is needed, in healthcare and across other industries, to effectively and efficiently capture skilled immigrant labor as one component in an overall workforce strategy. Moreover, any solution must also address the broader community impacts on housing and public-school capacity. Industry leaders might look to historical precedent when steel corporations and other industries built “company towns” to attract and accommodate large numbers of migrated workers. Reviving this old, but effective, model may create “both a profitable, sustainable business, and [make] positive social and economic impacts on the community.“14

America must apply various strategies to meet the looming workforce shortages ahead, and capturing skilled immigrant labor will be one important component. Instead of approaching immigration as a mitigation problem, businesses, policymakers, and educational institutions can adapt and collaborate to effectively leverage immigrant workforce opportunities. By partnering together, American leaders can turn immigrant opportunities into a reliable source of workforce growth.

References

Fix, Michael, Jeanne Batalova, and José Ramón Fernández-Peña. “The Role of Immigrant Health-Care Professionals in the United States during the Pandemic.” migrationpolicy.org, December 3, 2020.

Guevara, Tom, Abbey Chambers, and Drew Klacik. “Strategically Building a Workforce: PPI Policy Brief.” Public Policy Institute, Indiana University, June 2022.

“Health Workforce Projections | Bureau of Health Workforce.” Accessed October 20, 2024.

Kilmer, Brandi, Nicole Taylor, and Sky Jones. “Refugee Physicians: An Untapped Resource.” Their Story is Our Story, n.d.

Lichtenheld, Adam, Natalie Chaudhuri, and Sigrid Lupieri. “Resistant to Reform? Improving U.S. Immigration Policy Through Data, Evidence, and Innovation.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 28, 2024.

Lightcast. “The Rising Storm, a Lightcast Demographic Drought ...” Lightcast. Accessed October 18, 2024.

Plesch, Valerie. “Virginia Bill Would Give Alternate Licensing Path to Foreign Doctors.” The World from PRX, March 14, 2024.

Reagan, President Ronald. “Statement on United States Immigration and Refugee Policy.” Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. National Archives, July 30, 1981.

Sabet, Cameron, Mohamed Khalif, Nguyen Quoc Hoan, and Sarah Kureshi. “Supporting International Medical Graduate Workforce Integration in the 2024 US Election.” Family Medicine, 1.

Spring Institute. “Colorado Spring Institute for Intercultural Learners.” Accessed October 20, 2024.

UCLA Health. “International Medical Graduate Program,” n.d.

University of Minnesota Medical School. “IMG Program (BRIIDGE).” Text, December 9, 2019.

The Refugee Physicians Advocacy (RPA) Coalition is working with healthcare institutions, partner organizations, and lawmakers in Virginia to develop relevant re-training programs and changes to state licensure to strengthen the health workforce with International Physicians. We encourage industry leaders and educational institutions to invest in international physicians and other skilled refugees as one resource to help solve the U.S. workforce shortage.

Learn More

Reagan, “Statement on United States Immigration and Refugee Policy.”

Lightcast, “The Rising Storm, a Lightcast Demographic Drought ...,” 33.

Lightcast, 19.

Lichtenheld, Chaudhuri, and Lupieri, “Resistant to Reform?”

“Health Workforce Projections | Bureau of Health Workforce.”

Sabet et al., “Supporting International Medical Graduate Workforce Integration in the 2024 US Election.”

Lightcast, “The Rising Storm, a Lightcast Demographic Drought ...,” 39.

Fix, Batalova, and Fernández-Peña, “The Role of Immigrant Health-Care Professionals in the United States during the Pandemic.”

Kilmer, Taylor, and Jones, “Refugee Physicians: An Untapped Resource.”

Plesch, “Virginia Bill Would Give Alternate Licensing Path to Foreign Doctors.” updated to reflect current figures as of the date of publishing.

“International Medical Graduate Program.”

“IMG Program (BRIIDGE).”

“Colorado Spring Institute for Intercultural Learners.”

Guevara, Chambers, and Klacik, “Strategically Building a Workforce: PPI Policy Brief.”