We Took Our Own Path

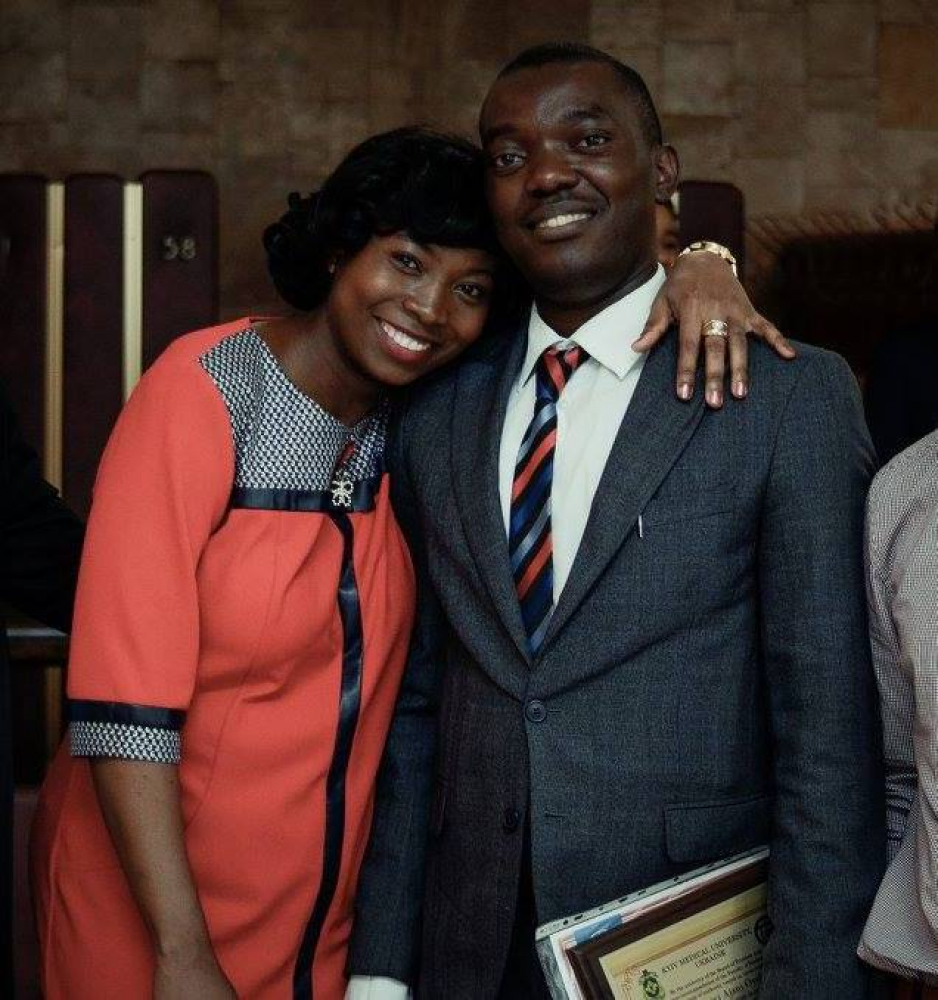

A Nigerian couple, medical doctors, living in Ukraine tell their harrowing story of how they fought to stay together with their three kids.

My name is Oluwaseyi Ajani-Oyebanre and I’m from the southwestern part of Nigeria. The present conflict first touched me on February 24th. I was asleep and my phone was ringing. My friend was calling to say the bombing had started. I knew that troops were along the border, but

Nobody thought war would actually happen. That's just the truth. We were all living our lives normally.

I am a medical doctor and I resided in Ukraine, from 2010 to 2022. I have three wonderful kids and a precious spouse, Emanuel. He’s also a medical doctor. We met in Ukraine when we studied together in medical school.

Originally we lived in the eastern parts—Donetsk and Luhansk—and we spoke Russian. But in 2014 when things started heating up, we moved to Kyiv.

When the war started Emmanuel was in Odessa for a medical conference, so when people started calling me, I was worried about him, but he was able to come back that same day.

Everybody was running out of Kyiv, but I felt like I should stay.

We remained in Kiev for nine days. I know everyone will be wondering—why did you stay for nine days? Well, we run a travel agency—we bring medical students to Ukraine—and we still had some students in Kyiv. Their parents had asked us, “Doctor Emmanuel, please don’t leave my child behind.” We were able to make sure all our students were well taken care of. We wouldn’t leave without them.

Their parents had asked us, “Doctor Emmanuel, please don't leave my child behind.” We were able to make sure all our students were well taken care of. We wouldn’t leave without them.

I soon discovered another reason [we stayed]. A close friend, who is our manager in Nigeria, had come to Ukraine for vacation and was caught in the conflict. [H]e sent Emmanuel a text message saying, “I was shot five times.” I think God wanted us to stay behind so that we could get him out. He was in the hospital and he didn’t speak the language. When Emmanuel heard about it, he immediately went to the hospital. He spoke with the doctor. They could only discharge him after five days. So we had to wait.

Our friends, family, and everybody was calling and asking why we were not out of the country. But we had an obligation. We prayed about where to go. Our time there gave us clarity of mind. We realized we had our own path.

Eventually we got train tickets for our manager, for another medical student named Jesse, and for our family members, and we all left on the same day for Uzhghorod. We witnessed a lot of miracles along the way.

On the train from Kyiv they were letting women and children on first. Our manager who had been shot entered first, and then I entered with the kids. There was a conductor and someone controlling the crowds who was allowing people to enter one at a time.

After some minutes I realized Emmanuel was not on the train. So I left my children to find him. When I got outside, the men at the door were telling people that the train was full, and that the men couldn’t come in.

Emmanuel was outside, and I was alone with three kids and someone in need of medical attention. I was furious. I said, “What is the meaning of this? Emmanuel is getting on this train!” I know by law that he’s allowed to travel, and moreover he’s neither Russian nor Ukrainian. So I started speaking Russian, and I started shouting, “Emmanuel, get on this train now. He’s the father of three.” But the man at the door kept shouting, “No, the train’s been filled up.”

You know what I did? I sat on the stairs of the train at the entrance and said, “This train is not going anywhere if my husband isn’t on it.” The man thought I might be scared because he was holding a gun—oh please! I’m from a military home. I’ve seen guns. I wasn’t scared.

I told him, “If Emmanuel doesn’t get on this train—he’s the father of three—how do you want me to cope on the long journey without him? He has to get on this train. If not, this train is not moving.” He thought it was a joke. But I sat down so no one could enter. When he realized that I was not joking, he said, “Who is your husband in the crowd?” I said, “That is him. He must enter this train right now.” And he said okay, he can go with you.

I’ve noticed that people are not empathetic to women who have to leave their spouse behind. It’s very difficult. Right now I see lots of women, Ukrainian women, with just children. By law their husbands are not allowed to leave the country; maybe they have to volunteer, and maybe some are even fighting in the war. I think a lot of people are overlooking the fact that they need to empathize with these women. Women are dealing with emotional trauma and they have to deal with kids alone, it’s not easy.

We need to take care of each other.

I remember the night we got to Austria, to the Hofbauers—that was the family that housed us for a few days. We were really tired. I finally slept without the noise of jets and bombs. We were well taken care of—and these are people we don’t know. They provided everything we needed—information, how to go about getting settled down, documentation—they were really there for us.

The most difficult part of this transition is that Ukraine was already home for us. I had all my children there, and we had already integrated into the system, we learned the language, we learned the culture. Walking away from all of that, to me, is hard work. It took us almost eight years in Ukraine, and I’m like, I might get to spend another ten years integrating? It’s hard leaving the known for the unknown.

Our team members obtain informed consent from each individual before an interview takes place. Individuals dictate where their stories may be shared and what personal information they wish to keep private. In situations where the individual is at risk and/or wishes to remain anonymous, alias names are used and other identifying information is removed from interviews immediately after they are received by TSOS. We have also committed not to use refugee images or stories for fundraising purposes without explicit permission. Our top priority is to protect and honor the wishes of our interview subjects.