The Rohingya: Cultural Celebration, Human Connection, and Every Day Life

How one photographer uses his art to build connections with people around the world.

My name is Daniel Bainbridge. I am an Aerospace engineering graduate from New Jersey. I originally planned on pursuing a career in space technology, maybe something with satellites, but didn’t have a clear goal in mind. It was around this time that I discovered my passion for photography. I had always been passionate about art growing up, so much so that my parents thought I’d become an artist, until I developed a strong interest in math during my teenage years. It seems, however, that this passion for art, in the form of photography, found its way back to me.

Now I find myself traveling the world, photographing people and putting together collections of photographs that portray humanity, touching on cultural celebrations, human connection and everyday life. As someone who grew up socially anxious and introverted, traveling is an opportunity for me to free myself from the restraints of how people I already know expect me to act and to act solely how I want to. This allows me to open up to people and have experiences I couldn’t have before, which has become the driving force behind my current project.

I travel with no plan. I like to keep my plans open and follow the suggestions of the people I meet, especially to places I never would have considered on my own, where interactions feel the most sincere. Sometimes I’ll arrive in a random town I found on Google Maps, ask locals what there is to see, and explore. Because people aren’t used to travelers doing this, they become curious and invite me into their homes and lives. They show me their communities and share their stories. This, to me, is what every traveler should experience, and is the single best way to truly experience someone’s culture

My goals have changed over time, but one thing has remained constant: I want to experience and photograph the kindness and beauty I find in people.

I learned about the Rohingya when I arrived in Bangladesh. Someone had mentioned to me that the largest refugee camp in the world is near Cox’s Bazar, and I knew I had to go. I wanted to meet the people there and hear their stories. I went with a friend and a local guide who spoke Chittagonian, which made it easy to navigate and communicate. Since it was just the two of us and I only carried a small camera, we were able to experience the place in a more intimate way, which would have been difficult with a larger crew.

Something that you hear a lot is that people with nothing have the most to offer. I already knew this to be true, but upon meeting the Rohingya, I experienced a kind of generosity that will always stick with me. Immediately after entering the camp, we met an 18 year old boy named Anwar who offered to bring us to his home. It was a small two-room building made of bamboo and plastic sheeting. Inside, an elderly man lay on the floor hooked up to IVs, barely conscious. The two of us sat in some chairs beside him and the boy brought us tea, an energy drink, and cake. We tried to refuse, but he insisted. His grandmother had noticed us from the other room. After a brief exchange in Chittagonian, my guide turned to me with a troubled expression and said, “They want to give us lunch.” I tried to decline politely, but they wouldn’t accept no for an answer. Refusing would have been disrespectful, so we accepted, and within 20 minutes we were sitting together on a plastic mat on the floor in the other room eating food. We had rice, fish and beef. I imagined that this was only for really rare, special occasions. As we ate, more family members stepped in and out of the small home to greet us and see what was happening, and a small crowd began to gather at the doorway. Anwar’s grandmother told my guide that the man lying in the other room was his grandfather. He was seriously ill but had been turned away from the hospital because they claimed he was “already dead”. Rohingya refugees are routinely denied treatment at hospitals outside the camp, and the limited medical facilities inside offer almost no real care. The family had been lucky, as my guide explained to me. They escaped genocide from Myanmar and crossed the Naf river about 8 years ago and came to this refugee camp. Their relatives and friends all died and they were lucky to have made it out. While my guide translated their story, they kept yelling at me to eat more. One thing he translated to me that I will never be able to forget was his grandmother saying, “If your stomach is happy, you’re happy.”

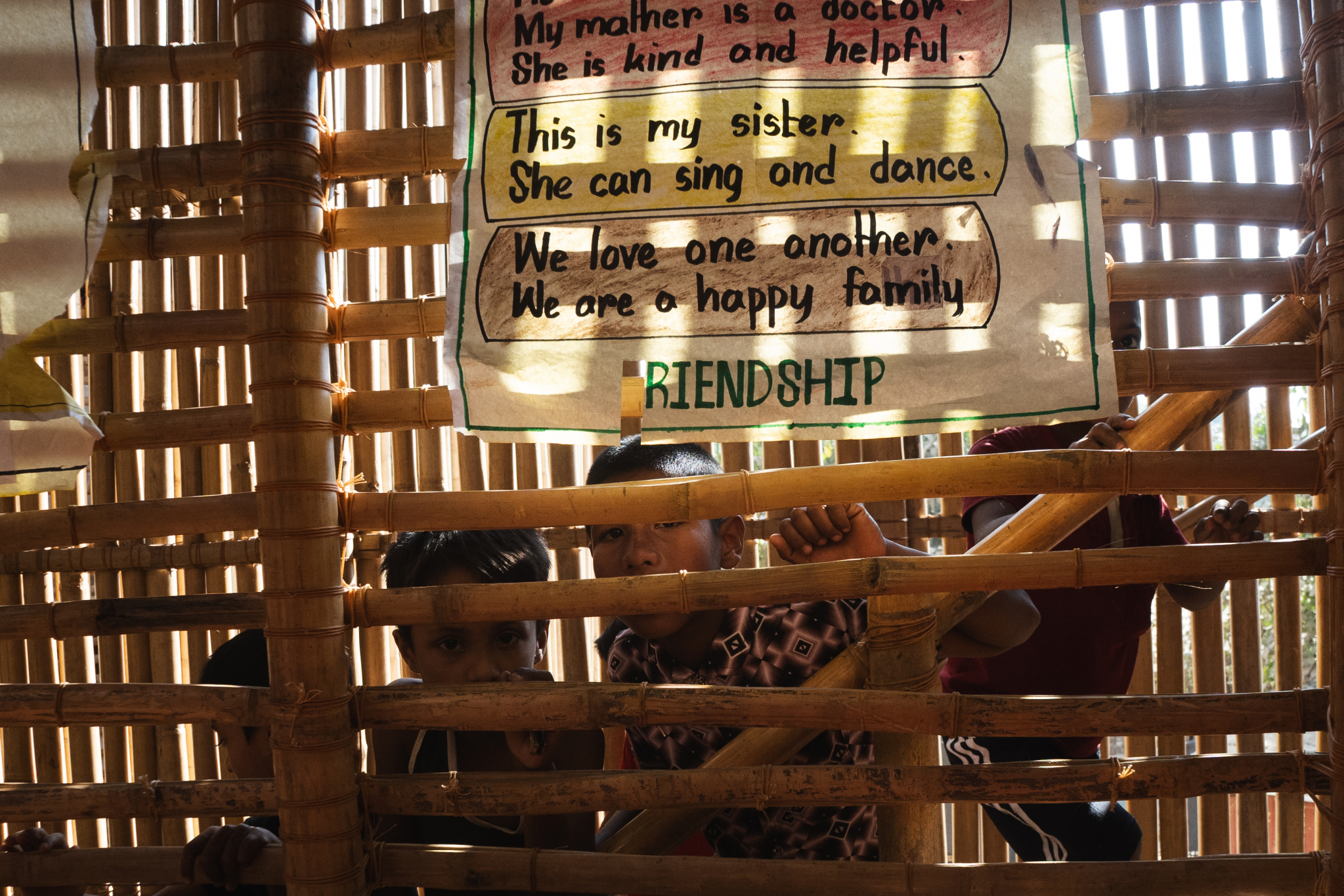

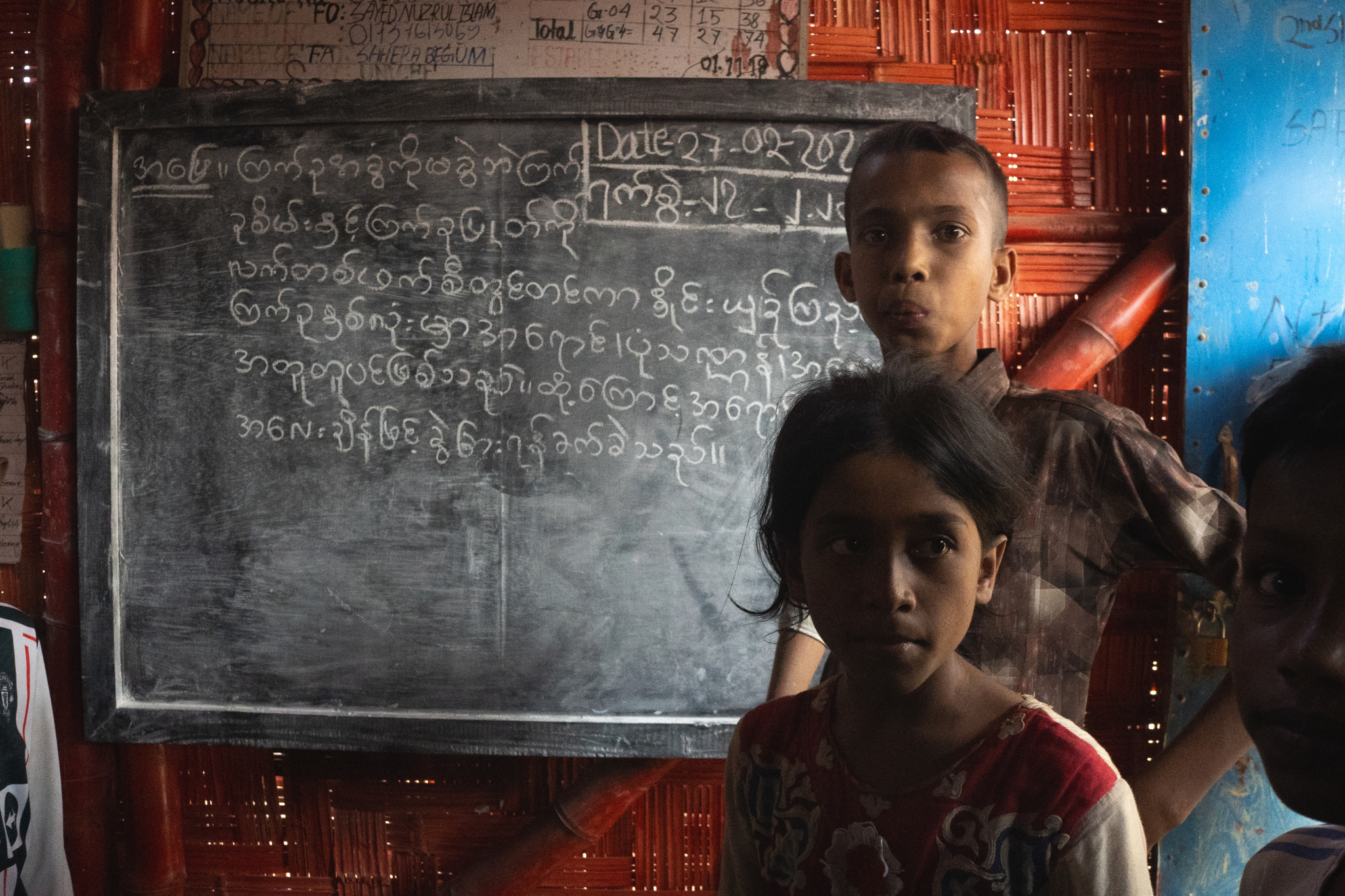

Anwar offered to show us around his camp. In Kutupalong, there are over 38 camps. We saw only parts of one and we walked around for hours. The first thing I noticed immediately was the number of kids. There were many primary schools but no higher education, and since refugees are legally barred from working outside the camps, young people have little to no career prospects. It didn’t take long for me to realize that many of the children had little understanding of their situation. Many were born into the camp and have never known anything beyond it. They don’t even know what they don’t have. They were just kids, laughing and playing the way all kids do.

With this project I want the world to know how similar everyone is, in this case, how similar we are to the Rohingya. This became more relevant to me the more I walked around.

The Rohingya want what all people want: they want to enjoy each other's company, feel cared for and be understood. They want to talk and make jokes to people, tell stories, share their food and their culture, their music, their religion, talk about their work and their families. I think if everyone saw this, the world would be more forgiving and these people would receive the care they need.

I’m not sure why this is so important to me. It just is. If I could make some sort of impact on the world, I would want to inspire others to set off on an adventure with a similar purpose and spirit; for them to see the success of this trip and project, and, by doing so, develop the interest and curiosity enough to go meet extraordinary people, approach everyone with the same level of empathy and kindness, and fully immerse themselves in the experiences and connections the world will surely give them.

Our team members obtain informed consent from each individual before an interview takes place. Individuals dictate where their stories may be shared and what personal information they wish to keep private. In situations where the individual is at risk and/or wishes to remain anonymous, alias names are used and other identifying information is removed from interviews immediately after they are received by TSOS. We have also committed not to use refugee images or stories for fundraising purposes without explicit permission. Our top priority is to protect and honor the wishes of our interview subjects.