Jews for Justice: Healing the Here and Now

Jews for Justice and Paying it Forward

We embark on this journey from the bottom in the search of this lie of an “American dream”. I think that the “American Dream” is an assumption rather than a statement. It assumes that you start at zero, but we start negative.

My name is Eddie Chavez Calderon. I am formerly undocumented, originally from Mexico, and I currently live in Phoenix, Arizona. For the past five years I have been a part of Jews for Justice.

Judaism started to click when I was in middle school. I heard about the Holocaust, and the intense resiliency of the Jewish people. In high school, a teacher really started to help me and wouldn’t stop. I was struggling, as an undocumented teenager. I couldn’t have a license and my future was unknown. Why should I care about turning in an essay when I could get pulled over and deported? Education was last on my list. But this teacher would not let me go. I asked her why she cared. I expected her to say something about getting to heaven.

But she said, “Because I’m Jewish.” That was her answer. “I’m Jewish.”

I was like, “what does that even mean?”

She said, “My job is to help and repair the here and now because it’s the right thing to do.”

I asked, “You’re not doing this for you?”

She said, “No, I’m just doing what we do.”

I was shocked, and it started fueling the fire of Judaism. With the help of mentors I brought my faith to protest, my faith to dinners, my faith to reuniting families, my faith to educating people. It was just gorgeous. And that’s the foundation of who I am within my Judaism. I think the absence of faith can lead to a quick route to burnout in the work that we do.

Arizona Jews for Justice was founded by Rabbi Shmuly. He looked at the implications of the injustice, here, in Arizona, with vulnerable populations and I began to help him organize. In 2018 when migrants were being released onto the streets, it was 120 degrees. I had a group of Jewish grandmas making food. I had doctors, I had lawyers. I had Jews from China, sending me sweatshirts, underwear, and packaged goods. I had Jews from Russia sending me stuff.

You see the Torah, tells us more than 36 times how to treat a stranger. You can’t just tolerate a stranger. No It goes deeper. It says you must love and protect a stranger for you were once a stranger.

What I’m trying to do at Jews for Justice is level the playing field. I’ve been blessed to work at Jews for Justice for almost five years. We’ve been able to support hundreds of families here in the Phoenix area that come through Nogales - the exact same place I came through. I’ve been able to go through the desert that I walked through and drop water and food for migrants.

When we look at resources, we try to take a step back and think, what is my intent and what is my impact? My intent may be to provide the best support to asylum seekers, but if I give them 50 pounds of clothing and raw food when I know they’re traveling to New York, Is that helpful?

So we ask them what they need. Migrants have a better understanding of migration and the resources that they need than we do.

They need access to snacks that are carryable and nonperishable, activities for children that they can carry through TSA, and technology that will help them connect to their families. We try to make sure that our resources have the greatest impact rather than the greatest intent.

Prior to 9/11 the border was very fluid. Folks could come in and out. After 9/11, the Border control began to deter people with fear.

Now, our current system empowers the cartels. When push comes to shove, people are going to show up and people understand that if they go back, it’s death. They have no other choice. So they’re going to do whatever it takes to get their families to safety. I encourage everybody to go down to the border. Go into the desert and ask yourself, “People were willing to do this? If people are willing to do this, how bad was it where they are from?”

And family separation hasn’t stopped. Males will get separated from the women and children. And I’ve seen horrible cases where a child is 17. He’s still a child. And just because they see that he’s gonna be 18, they move them to an adult facility, separate them from the mom and the dad. The parents are released and now they’re scrambling to figure out what detention center this child is in.

I think this new asylum process of looking at Venezuela and saying no, and looking at Haiti and saying no, but other countries, yes is incredibly painful. But with the expansion of Title 42, I think there’s going to be major implications for asylum seekers coming into the United States.

I think the United States has an abundance of resources. We're a globalist in resources, but our response to helping people is third world. There's enough resources for everybody. We just have to take a step back and have a little humanity.

We need a more equitable process. I think one of the most equitable ways that we can start is to provide a tiered base approach. For example, start with a work permit, from the work permit provide a pathway that you could get residency, and from here, here’s a pathway that you can get citizenship, you know–but aid that pathway, don’t just say “do it” and not have anything to help.

As far as the surge, people are handling it already. Give those people resources to continue to do what they’re doing more efficiently. Let people doing compassionate work continue, and let law enforcement deal with the actual nefarious crimes. Don’t let them handle single moms with babies. Leave that to the organizations that have facilities and have experience, have resources.

At a recent interview, a woman described this concept of coming to the United States as an asylee. And she said it's like I'm at the cliff. And there's a big long gulch in front of me full of water and alligators and they're saying, okay, here you go. Here's your asylum. You get across. And there's no bridge. There's no rope. There's nothing. There's nothing except for this goal. And what she has to do to get across is going to leave her so battered, so damaged. That once she arrives on the other side, that trauma leaves her less of a person, less of a contributor to our community.

It’s insane. It’s like, Hey, your next asylum court hearing is in four years. By the way, you can’t work because if you do, you’re deported. And don’t mess up. Don’t get a parking ticket. Don’t jaywalk. Don’t have an issue with your spouse or yell at your children. You know, it’s insane. It’s a system that is set up and curated to fail.

If we put in these humane systems we would have stronger communities and better contributors because we’ve made a natural pathway that would be doable. After all, we know that refugees and migrants are the fastest business starters in the US. That brings economic growth. Imagine how much more growth we’d have if the process was less traumatic. Even now the undocumented community is contributing so much money to our communities and [they] have zero benefit. It’s up to us right now to make sure that we create those structures that allow people to have a thriving, booming economy that ultimately ends up helping every single one of us.

There is a myth that undocumented immigrants are taking resources from our country and that’s simply not true. Immigrants and asylees and refugees and undocumented communities give back so much more than they consume.

When I'm passing out snacks, migrants will take exactly one thing that they desperately need and they look around to make sure that everybody else has access to one thing. I can even hand them two things, and they will give it back to me just to make sure that the next person has something.

If you want to help, start by educating yourself and others. Without education, fear starts to set in and fear builds into hate and violence. So start with a barbecue. Let’s actually talk to some migrants. And from there start to ask yourself some questions:

What are some community-based resources?

Do I speak two languages?

Can I provide a little bit of my time? An hour, 30 minutes, 15 minutes on a call of translation?

Do I have an extra bed?

What do I have in excess that I can provide?

And finally, I think there needs to be a community approach that reignites the joy of helping people. I feel like our community has done such a good job of polarizing and politicizing supporting vulnerable communities that we have forgotten the roots of joy that come from supporting the most vulnerable.

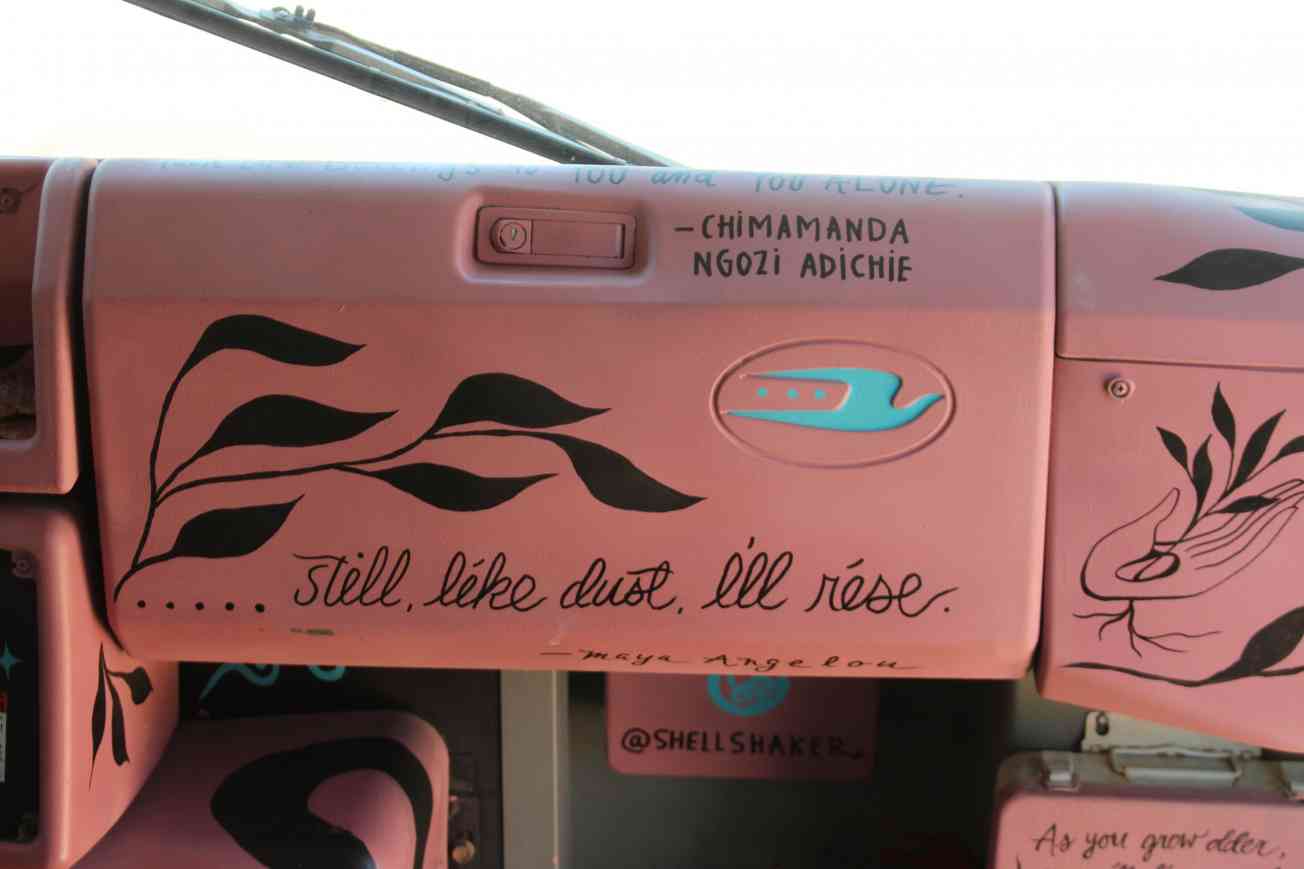

We need to not pity migrants and asylum seekers. They have made a journey many of us would not survive. We need to see their bravery and resiliency. They are like the desert plants. It almost doesn’t make sense that we survive. And still, we’re beautiful, we’re thriving, we’re brave. We’re bold. We’re here.

Read about Eddie’s childhood as an undocumented American:

Growing Up An Undocumented AmericanOur team members obtain informed consent from each individual before an interview takes place. Individuals dictate where their stories may be shared and what personal information they wish to keep private. In situations where the individual is at risk and/or wishes to remain anonymous, alias names are used and other identifying information is removed from interviews immediately after they are received by TSOS. We have also committed not to use refugee images or stories for fundraising purposes without explicit permission. Our top priority is to protect and honor the wishes of our interview subjects.