If You Hear People Telling You That You Cannot Do Something, Make Sure You Do It

A refugee from Iraq defies expectations

My name is Abeer Riemann, and I am from Iraq. I lived there with my very big family. I have eight brothers and seven sisters—fifteen total. We are a community and are all educated. Most of us have master’s degrees or doctorates. I got a master’s degree in English Literature and was an English teacher back home in Iraq.

My refugee story started when five of my brothers worked with the American military as interpreters. When they started, it was very hard. If people knew that we were working with the American army, they would think we are not good people or something like that. So people started chasing us and throwing CDs in our yard. The CDs were recordings of how they kill a lot of interpreters, beheading them. They record it and throw it in our yard to tell us, “Hey, we know that your brother is interpreting for the Americans, so we will kill him too.” It was a death threat.

We always, every second, lived with fear and worried about my brothers. They were all on different military bases. When we heard news about each brother, we felt like, “Oh, okay, he’s still alive.”

One day, one brother said he was coming to visit us. He was working in Fallujah. When he came on his way home, we started to worry because he didn’t arrive, and we could not contact him. After a week, my brother called us explaining what happened. As he was coming to visit us, four cars surrounded him, and then they opened fire on him and killed the driver. My brother pretended that he was dead—just put his head on his knee. The bad guys took all the luggage, including pictures and information my brother had about our home. Then, the bad guys came back and shot everyone again to make sure they were dead. This time, my brother got shot through his bag. He called the base, and a helicopter came to rescue him. After that, the general helped him come to the United States, letting my brother stay with him in his home in Kansas. He was the first of us to come to America.

After that, the rest of my family applied for special immigrant visas or refugee status. One by one, people left for America. We said goodbye, and felt happy for them because they’re going to a safe place, but we still worried about ourselves. We didn’t know what was going to happen.

I finally came to the United States in 2012. The rest of my family is here except for one sister. We are waiting for her to come.

Now that we are here, we’re safe. We live our dreams, and we appreciate the life here. We are very happy. In Kansas City, the people are very welcoming. They make you feel at home. The first time I went shopping, people would say “hi” to us and smile. We were confused at first, thinking, “Do the people here know us? Why are they smiling?” We are very grateful for being here in America and specifically in Kansas City.

Of course, we still miss our country. We have a lot of memories there. I was in the very north of Iraq—it’s all mountain and snow, even more than here. We learned and played a lot there, and we have a lot of friends there. So, of course we miss our country, but, at the same time, we didn’t feel safe. And there were not a lot of opportunities for work or for education. So we are very grateful to be here in America.

Still, there are many things to adjust to. For example, Americans cannot pronounce my name. My name—Abeer—is an Arabic name. It means the fragrance of flowers. As I started to connect with people in the community here, I realized it’s hard for them to pronounce the first letter of my name. So I told them to just call me “Abby” to make it easy. But it’s not easy for me to simply change my name because it is the name that my father gave me. I didn’t like to change my name just to make other people feel better. So I am keeping my name Abeer, even if people cannot pronounce it.

Many of the changes are good. In America, there are many opportunities to prove yourself and to show what you can do. My mom did this. She had never been to school in Iraq, but when she came here she started going to school every single day. She learned letters and learned how to read in English. Although people told her she could get a medical waiver for the citizenship exam, she said “No, I’m not going to do that. I am going to study.” She proved herself and challenged expectations. And she did it. She passed the test.

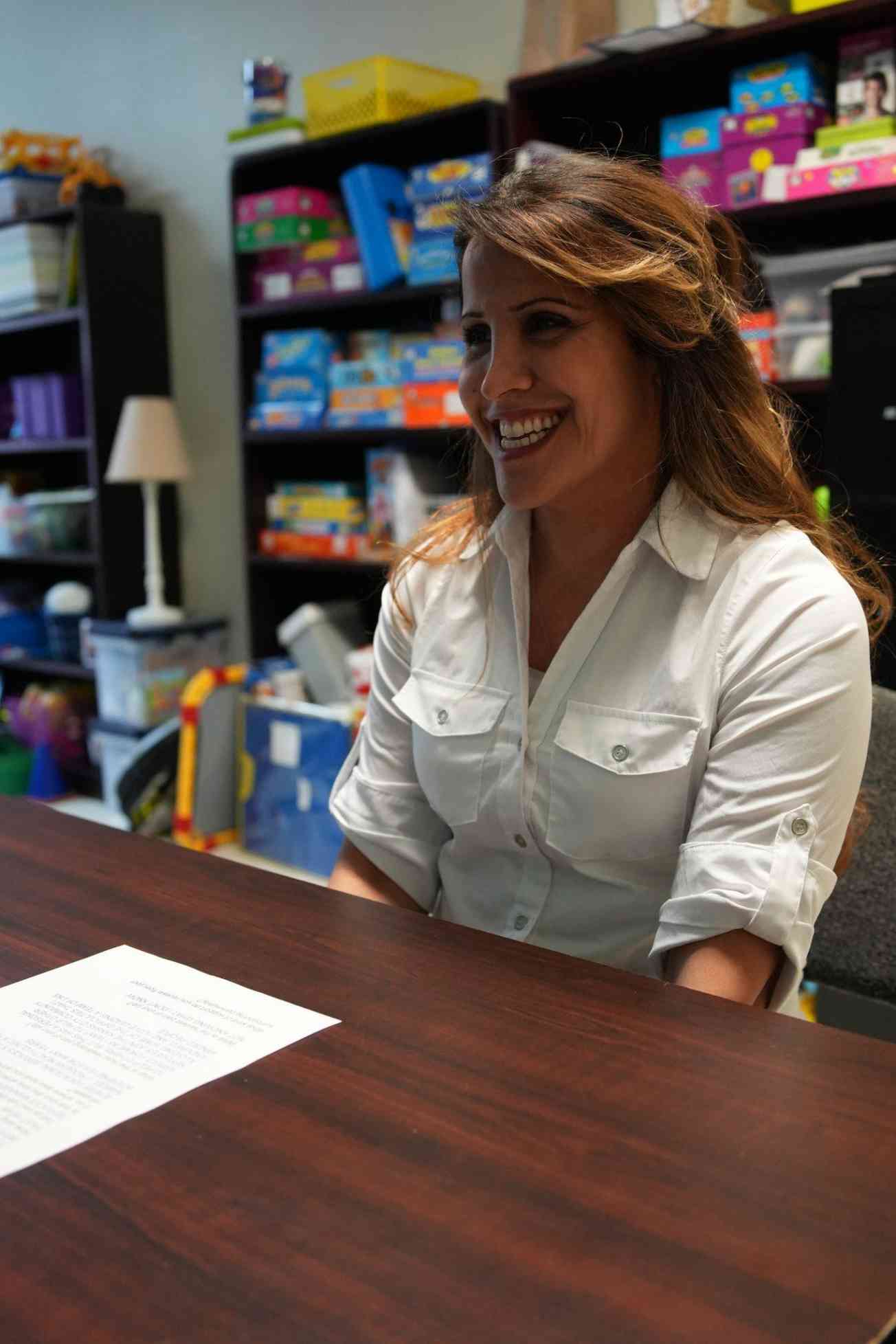

I also challenged expectations. When I came here, I had a master’s degree, and I wanted to become a teacher. But people told me I needed to start all over. If you hear people telling you that you cannot do something, make sure you do it.

So, I became a teacher for refugees. I lead a team of teachers at Della Lamb. We teach refugees English and digital literacy so that they can find employment. I am here to protect these people from feeling like they cannot do anything.

Never underestimate the refugee. They have a lot to give. They have dreams. They have goals. They want to reach these goals, but didn't get the opportunity in their country. So they are here now, and they have this energy to give and prove themselves.

Even if I didn’t have opportunities in my country, now I am in the right place. I am still alive. I didn’t die there, so I have to give, and I have to reach my dreams.

Our team members obtain informed consent from each individual before an interview takes place. Individuals dictate where their stories may be shared and what personal information they wish to keep private. In situations where the individual is at risk and/or wishes to remain anonymous, alias names are used and other identifying information is removed from interviews immediately after they are received by TSOS. We have also committed not to use refugee images or stories for fundraising purposes without explicit permission. Our top priority is to protect and honor the wishes of our interview subjects.