During a series of interviews with forcibly displaced people, and in discussions with other like-minded NGOs, Their Story is Out Story (TSOS) recognized significant gaps in designing and providing trauma-informed therapy for individuals who have experienced displacement. These gaps were further reinforced by legislation and policies that did not appropriately address the mental health needs of resettled populations. To address these gaps, in 2021 and 2022 TSOS interviewed four mental healthcare professionals who each work in a different field of mental healthcare, and as such provided a broad picture of the challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned.

The following interview with Dr. Maria José Colmenero Scheible discusses challenges and concerns specific to the work she has done with the refugees resettled in Germany.

Please tell us a little bit about yourself and your background.

My name is Maria José Colmenero Scheible. I’m from Spain, married to a German scientist for 29 years. I have a practice based in Germany. I'm a clinical psychologist, behavioral therapist. I do have a specialty in neuroscience PhD studies. I love to learn and I love the field of health and mental health a lot.

How did you get into the field you are in? What drew you to mental health, in particular, helping people who have been displaced or people who are experiencing trauma?

I do not have a romantic answer to that. I had started my studies in Law in Spain, and then I got married to a German. Because it is foreign law, all my credits were not functioning the same in Germany. I wanted to study something that will be applicable in all other countries so I would never have that experience again. Instead I went to nursing school, and loved it. I enjoyed working at hospitals. In fact it became a passion of mine - working in the surgery room for a long time. And then I developed an allergy. And my boss, who was a great surgeon, said, “You seem like someone who can easily make change, you may want to change into the field of psychology.” And so I started my studies in the field of psychology and I really love it.

What are some of the lessons that you've learned about the trauma experienced by refugees?

This is a very important question, because as professionals we witness a lot of human suffering, and I'm very thankful for the persons that are willing to share with me their experiences. For me, trauma has transformed me to be able to be in the therapeutic room with another person, witnessing their experiences and sharing different points of view. These things have been challenging on one end, because you need to adapt your skills to the trauma and refugee field. You need to be kind of brave because there is not a lot of rich research in this field, sadly. And on the other hand, it has transformed me in a profound way. And I'm always amazed about the human ability to heal and to recover. As a nurse, I saw this, the human body recovering. What a surgeon or a nurse performs assists the process, but the human body itself has the ability to recover and to heal. In a similar way, the human mind also has this ability to heal. I'm always amazed by it.

That is such a hopeful message. You talked a little bit about having to adapt your skills. Is that based on where somebody is coming from, or the journey they have experienced? Tell me about the adaptations that you've had to make in your work with displaced people.

Well, I want to say that many of my colleagues are doing amazing work, but I cannot understand why so many don't feel like working with refugees. And one of the most important points where I feel a little bit lost is that we don’t have a lot of research, like data that is solid. If I'm working with trauma, I have my model. And I can apply these models, and it gives me a kind of security that I'm doing the right things. If you are working with refugees, you need to be very flexible and be able to adapt to this model. For example, usually if you do an assessment in the West, you may do it with a checklist at the beginning. You will hand a list to the patient in the waiting room and they will go do an assessment. An ADHD assessment is mostly a written assessment. But working with refugees, if you hand them a list, it may be challenging for them because for some of them, they may not have the literacy skills needed to fill out an assessment like this. When you are working with refugees, in my experience, they bring high levels of distress in the room. So I often need to slow down, and an assessment that might take me one session with another client might take three or four because I want to respect the person in front of me.

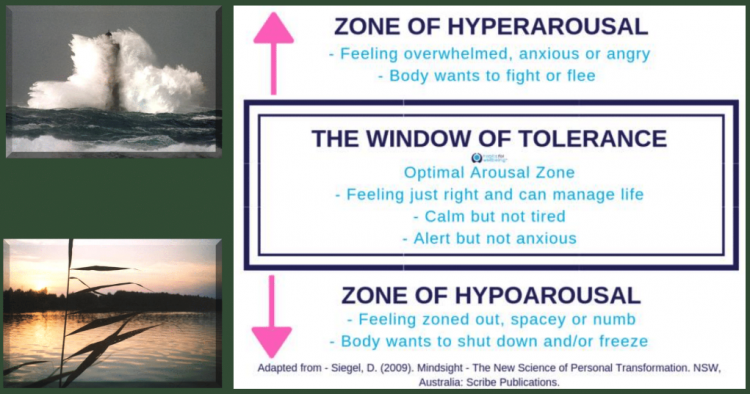

Many of my colleagues are like, oh, I need to understand a lot of the cultural issues of this client. And so, yes, of course, I think it's respectful, if you learn a little bit about it. But if I read a book about the client’s country, I will not know her better. I will just have some notions about the person. So, I always tell my colleagues to not be stressed about it. Gather some information, but at the end, therapy is something that happens between two humans in a therapy room. Cultural competency is important, for sure. But it's not something that should stop you from working with refugees. There are many things that you need to adapt to. You need to know if your patient is in a state where he can’t verbalize what happened to him. If they're not in what we call ‘the window of tolerance’, many refugees get rejected because of not being able to verbalize the torture they were suffering. But it's only because they are in a state of mind where they can't verbalize it. So while filling out some of the documents, asking for asylum, they may get rejected because they are not able to tell it.

Another thing is that we always say, the human brain is only able to see what he knows, what he's able to accept, right? But many of the experiences of the refugee, the torture and the suffering, are beyond imagination. So, the first response of a human brain (for the therapist) may be to think the client may be lying, and not accept what they are telling you. So we need to be very careful of this possible response in a therapy room. And I say, be curious and neutral and respect the person in front of you and understand that there are experiences that I have never seen.

Can you talk a little bit more about the stress that a refugee will then go through, especially if it's a mom in her 40s or a woman in her 50s? What does it look like? And how can we respond to it?

I think this is a very important question.

We know statistically, among refugees that are long-term in the European countries, they have a prevalence of 20% more at risk for mood disorders. This is maybe due to the drawn-out nature of the asylum process. Also, some of the refugees fear that if they go and contact a mental health professional that their asylum case may be rejected, so they do not seek the help they need.

In other cases, they have ideas of mental health settings in their country where they do not like to talk to another person. So the process can be really inhibited. And we know that the anxiety levels and the depression levels go higher being in the post-migration country.

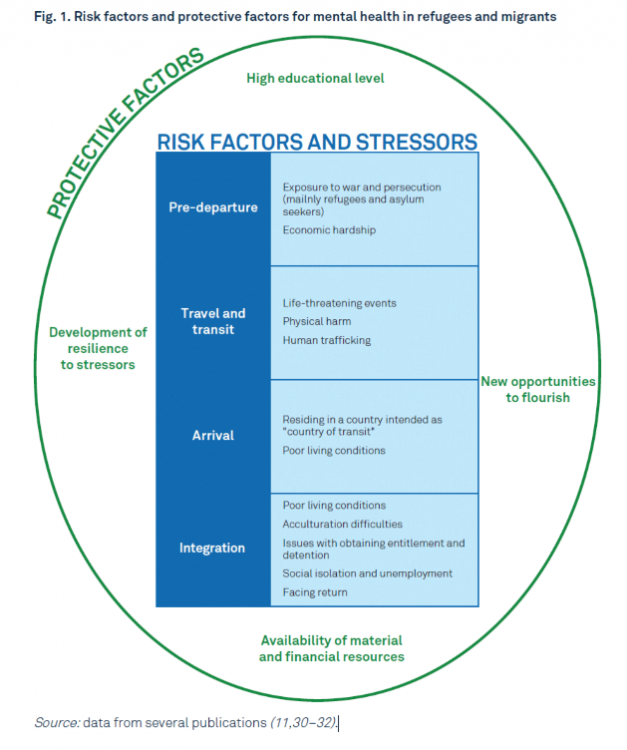

Here you can see the risk factors and stressors for our refugee in the pre-departure period. I think this is sad that this process can be so drawn out, and that we are not able to help refugees be in the window of tolerance to regulate themselves so they can be successful. This should be a very important task for us to accomplish.

This is a really good slide. The first stressor in the integration talks about the poor living conditions upon arrival and during the integration process. And not having the ability to actually have your own sort of a safe zone that you can kind of label as your own safe zone.

You are homeless and spaceless, and without control of your life and we know that anxiety type is the loss of control. You lose control and your anxiety levels get higher, and for a refugee, what kind of control do they have? In reality, it is very small when they are in the post-migration period. So if we are open and give opportunities so they can get control, this would be very helpful. We know about the protective factors for the mental health of refugees. In the research, we have too much very variable data and not very reliable data, sadly, but...

One thing that is clear across all the research is that if social integration is working well, this is the most protective factor for mental health.

Access to therapy is not the highest. I like to put myself in the middle of everything, but it's not me as a psychologist or a mental health professional. It is the neighbor or is the person nearby, it is social integration, and we all could accomplish this. And it will not be very expensive.

Can you talk about the successes that you've seen because of better social integration?

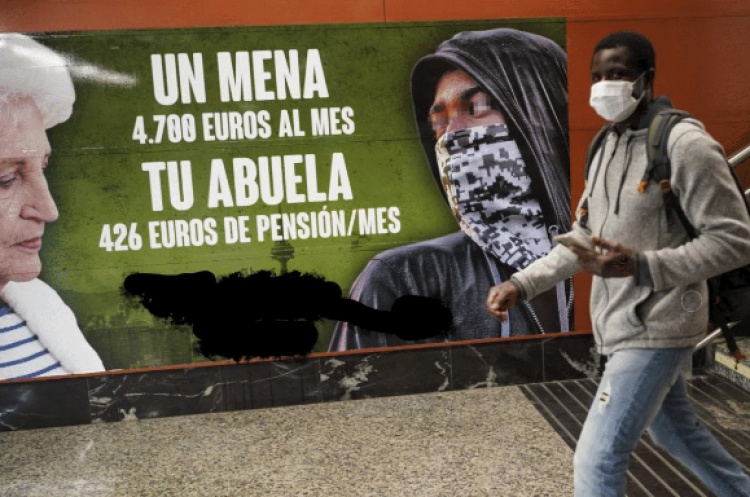

Well I think that is a healing experience when a human being approaches another one with respect. We need to be very aware of what we are saying about refugees. I would like to explain this a little bit with a slide.

While talking about social integration and the benefits of social integration, we need to talk as well about the risk of not being integrated and the impact on the mental health of refugees. This is a picture on the left that I took from a political party during the campaign. You get named as a refugee; it becomes a part of your identity and it takes three generations to adapt and for the social integration to happen in a positive way. In this case as you can see, it is a very sad publicity from a political party. I removed the party to avoid being political, but they will call “Mena”. Mena is Spanish for minor asylum seeker. They get a name, and as you can see in this picture, the minor asylum seeker is covered with the hoodie, with a mask, and on the left is the grandma, and they are comparing how much money a refugee gets compared to a grandma. This is extremely dangerous. It has a priming effect. The advertisement is placed at a metro station where every business, every person, every child that will walk through this station that sees it will be impacted, leading them to feel like refugees and “menas” are dangerous and are taking our money away. In Germany and in Europe, according to statistics, we only have 9% of all refugees, which is really low numbers. The worst scenario for integration is to give a wrong picture of refugees, like in this poster.

I notice that often young men or women may wear hoodies, and I asked all of them why. They don’t wear hoodies to perform robberies, or to be criminals, instead it is to protect themselves, because they are scared, and the stimuli and the stressors are too high. Wearing a hoodie acts as a shield against those things. So for the integration, we need to be very careful of the negative effects of the way we talk about or portray refugees. Words matter. And I was listening yesterday to an interview in Spain where there are like 8000 refugees, running to Ceuta. This is a Spanish territory in North Africa that borders Morocco. One person said, “We will defend our borders.” That implies to me like we are kind of at war and we are getting bombed or whatever. No, of course, there is a need to respect others, but we need to be very careful about our words. And being aware of this is a kind of social integration. It is respecting another human being and his experience, and realizing that I do not know enough to judge this person.

You talk about defending our borders. Sometimes we defend invisible borders at a school level, or at a professional level, or whatever that is to keep refugees out. How do we break those borders down?

Refugees come into a country needing to learn.

When we don’t understand neurology or how the brain works we can make really cruel decisions, as teachers, or as someone who wants to speed up integration. This is not my model, this is from a very intelligent psychologist, Dan Siegel who came to realize that there is only a window of tolerance where we can learn. This is the optimal arousal zone, when we have the feeling that we can manage or control life, that we are comfortable and excited. We are not bored or overly stressed. In this window of tolerance, social integration and learning takes place. We need to be in this window to be able to process some information. Well, sadly, many of our refugees come with high levels of distress, so they will be in the zone of hyper arousal, and their amygdala, which controls flight or fight, may be firing. Maybe it’s because their families are suffering, or they are left behind, or they don't know if they will be able to stay, or all these things. So, a large group of refugees will be in the zone of hyper arousal and going through a very, very long asylum process. No one can learn in this zone. It is like swimming against the current.

If we can help people to be in the window of tolerance, people will be able to integrate, to learn the new language faster, to be helpful for our communities, because every human being has something to bring into a new community.

Trauma is a very lonely experience. Every one of my patients who was traumatized feel alone in this experience. Going through the asylum process, they feel alone. And so if we want to integrate, we need to do it as a whole society.

How do we help a refugee understand and feel that they have that space, and that it's okay for them to say, I need that space? How do we help them overcome that fear of rejection, and the stress factors to feel like they can speak up for themselves?

Well, I think those are very important questions. So, the levels of anxiety are very high, and we need to slow down and show these refugee students as persons. For me, in my practice, it means that I take the time. And personally, I know that anxiety makes you speed up. Yet in this process, it's important to slow down, as you say, to take the time. And, of course, psycho education might be very helpful in this, like providing training for teachers. Education is one of TSOS’s objectives, and I think this is an excellent one. To provide understanding and training, not only for teachers, not only for professionals--we need it, for sure--but training for police, for example. And the core message is that...

When we are integrating, we are preventing mental health diseases.

Germany has an interesting model for this. What they did was to use mediators who were themselves refugees. And these mediators will be able to translate a little bit, and help them to maneuver through the legal system, the medical system, the mental health system. And so, it's some kind of mediation from the same country, and so the language skills and the language difficulties will not be a barrier. I think it's a very successful model.

There are wonderful professionals trying to do their best to integrate out there, and what I hope is that these will be more known. And that we can be helpful in de-mystifying some of the stigmas that some people do have about refugees, about the abilities of our countries to help refugees. I was very impressed when the German Chancellor said “Yes, we can do this.” I think it was a brave sentence. And this is one of the reasons I took the opportunity to say yes, I will offer some of my therapeutic space. I'm willing to do that as well. It is a milestone for Germany to say yes, we are integrating.

When we help them to integrate we are preventing mental health issues. That is a very powerful statement that how we help people integrate, how we help them have that social connection with others, and build again a network and weave themselves into the society, that is going to make or break them in the end. So this concept of social integration will actually help mental issues, trauma and loss. Wonderful.

1/3 of the persons who experienced trauma do not need therapy. They rebound by themselves to state of what we call Restitutio ad integrum, a latin terms that means going back to normal.

And then we work with the other 2/3rds. Like we may have patients we know who were raped, who were deprived of liberty, or experienced war torture, that may experience a kind of trauma, which consequences may be the personal disintegration. They may have dissociative states. Those people need a lot of help, and sadly it takes a very long time to realize who is in this kind of dissociation. People with amnestic dissociation may not be able to apply for asylum because they do not remember the torture. So we need to train government institutions. This is a very important part of helping some of these populations.

Thank you. Do you have time to just tell us about your other two slides really quickly?

Oh sure, the slide with a tree. This one is important to me. One of my traumatized patients sent it to me. And the kind of torture and abuse that this poor young man had suffered was devastating. He was in a dissociative state. While trying to explain this to him, he asked me, “Is it possible for me to go back to normal like nothing happened?” I wanted to be very honest to him and so I told him, “Look, there are some things you may need to learn how to deal with. They will stay there. But you will be able to do this.” I was very sure about it because he was a wonderful young man with a lot of resources and extremely resilient. And so, after a few days he sent me this picture and said, “Well, I know what happened to me. And I know it is there in my history and in my biography and I'm not able to erase it. But even a tree like this can grow with deep wounds.” And I was very impressed with his metaphor. And so I asked him for permission to share it. I felt it was a very important approach for those people who will who may keep some of the consequences of torture or abuse or consequences of traumatic experiences.

As the tree grows, it’s actually making that space for itself to exist. The important part is that by breaking through the trauma and the loss it's able to create that space with the bad things that have happened but making it a symbiosis rather than a parasitical type of a relationship. It's something that has strengthened you and made you a better person or stronger person or more resilient person rather than killed off your spirit. It's a very good picture.

I love it.

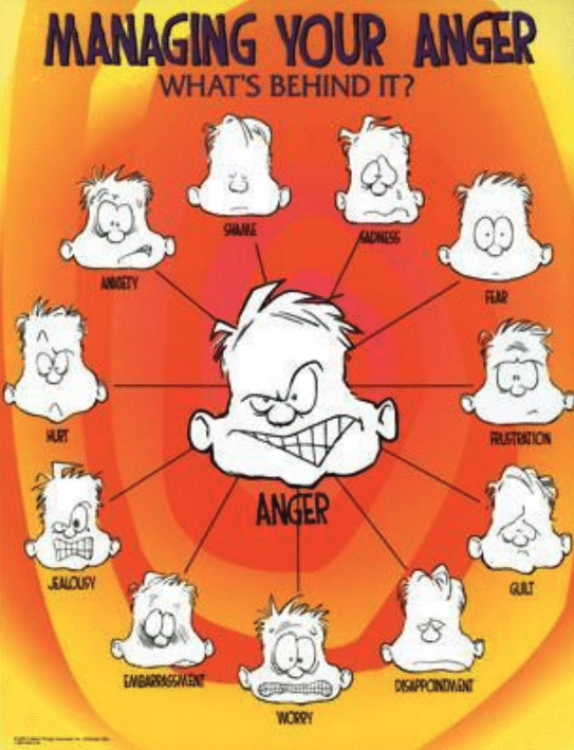

It would be a good thing to talk about this slide a little bit, because anger is a very normal reaction. Tell us a little bit about this slide, and the thinking behind it.

We know anger is a secondary emotion. There is a primary emotion behind it, there is a cause. So I'm helping refugees or whomever understand what is behind the anger. This is not my slide. Someone made this beautiful illustration and it may be extremely important for a refugee. If I called you an ugly name, which one will be the primary emotion and not the anger? What is behind the anger? What do you think?

It may be worry. It may be shame. It may be that they are hurt. There are many options, and we can’t help the person if we only address the primary emotion. We see the anger, but we need to look behind it. And honestly, this is not only for refugees. This also applies to general populations. If they see some pictures in the media and they get a message, like in the poster I showed you before, someone may get angry that his Grandma may not have the money and this foreigner will get it. And we can look as well behind the anger of the general population and see what's motivating this. Is fear behind something that I don't know? Is it worry that I don't know how we will make it? And so if we use this kind of model, we achieve an understanding of both human beings.

This has been a privilege to hear from you. We're so grateful.

I'm grateful for the work you're doing. Thank you very much.