Born with a cleft palate: The hospital giving hope to Rohingya children in Bangladesh

Their Story is Our Story (TSOS) is currently in Bangladesh to gather the stories of some of the 725,000 Rohingya refugees who have escaped extreme violence in Myanmar and who now live in Cox’s Bazar - the largest refugee settlement in the world.

Today, our fourth day of reporting from the ground, we visit HOPE Field Hospital for Women where doctors change the lives of Rohingya children by providing free surgery to repair cleft lips and palates - an orofacial cleft that causes problems feeding, hearing and speaking, as well as social stigma.

When we read and share the personal stories of individuals and families on their refugee journey - particularly of those stranded in camps - we think of ways in which we can provide immediate help: clothes, nutritious food, water purification tablets, education, and basic medical care. We often don’t think about the babies born - either before or in flight from Myanmar, or at Cox’s Bazar refugee settlement in Bangladesh - with significant medical conditions, like the cleft lip and cleft palate.

What is a cleft lip and cleft palate?

A cleft lip and cleft palate happen when the baby is growing in the womb and the baby’s face doesn’t join together properly. A cleft is a gap or a split in the baby’s lip or in the roof of their mouth (the palate). A baby can be born with one or the other, or both. Sometimes a baby might have one cleft, or they might have two: one on either side of their lip. Sometimes a cleft palate might mean that the baby has a small hole in the roof of their mouth, whereas sometimes they could have a gap running all the way along to the front of the mouth.

Why does this happen?

No one really knows why babies are born with clefts. It is thought to to be a result of a combination of different factors: genes, diet and environment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that smoking, diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy and certain medications can increase the possibility of a cleft lip or palate.

We do know that families with low socioeconomic status are mostly at risk, particularly those living in rural areas. Between 6,000 and 8,000 children are born with cleft lip and cleft palate in Myanmar each year, including many Rohingya babies.

What problems does it cause the baby?

Babies born with a cleft lip are more likely to be susceptible to ear infections and glue ear, which can affect their hearing. Those born with a cleft palate have difficulty feeding from the breast or bottle, because they cannot form a good seal with their mouth. Cleft lips and palates mean that the child’s teeth can not grow properly, and if left uncorrected then they are likely to have speech problems.

In Myanmar, children with cleft lips are often nicknamed A Pae Gyi (harelip), and many believe that the cleft brings bad luck. Even before the Rohingya were forced to flee their home country, surgery was not an option. Children faced stigma at school and then struggled to find work later on.

A mother’s worry

As a mum to two small children, I really struggle to contemplate the stress that the Rohingya mothers whose babies have been born with a cleft lip or palate must be going through. Our primal urge is to feed our babies - whether that be breastfeeding if we can, or bottle feeding - so that they survive, develop healthily and grow strong. My daughter, who is now five, was born with tongue tie. For weeks and days I watched, listened and felt her as she fought my breast, unable to latch until the problem was diagnosed. It was unbearable. She was too skinny. I was a wreck.

I was lucky. I lived in London, a developed city in the U.K. where all adults have the right to vote. I had easy access to medical care. The problem was quickly fixed. We were able to continue on our journey of new life together. But, the Rohingya have coped with enough; are still coping with enough. The anxiety of bearing a child with no guarantee of a healthy successful future is difficult for us to consider as we sit in our safe homes, with our families. The added pressure of a new baby struggling to drink milk to survive is unthinkable.

The hospital providing hope

A simple surgery can change the life of a child forever. HOPE Field Hospital for Women - the 24/7 Bangladeshi-run field hospital operating in Cox's Bazar refugee settlement - is providing free surgery to repair cleft lips and cleft palates. Ninety percent of those surgeries are for Rohingya refugees.

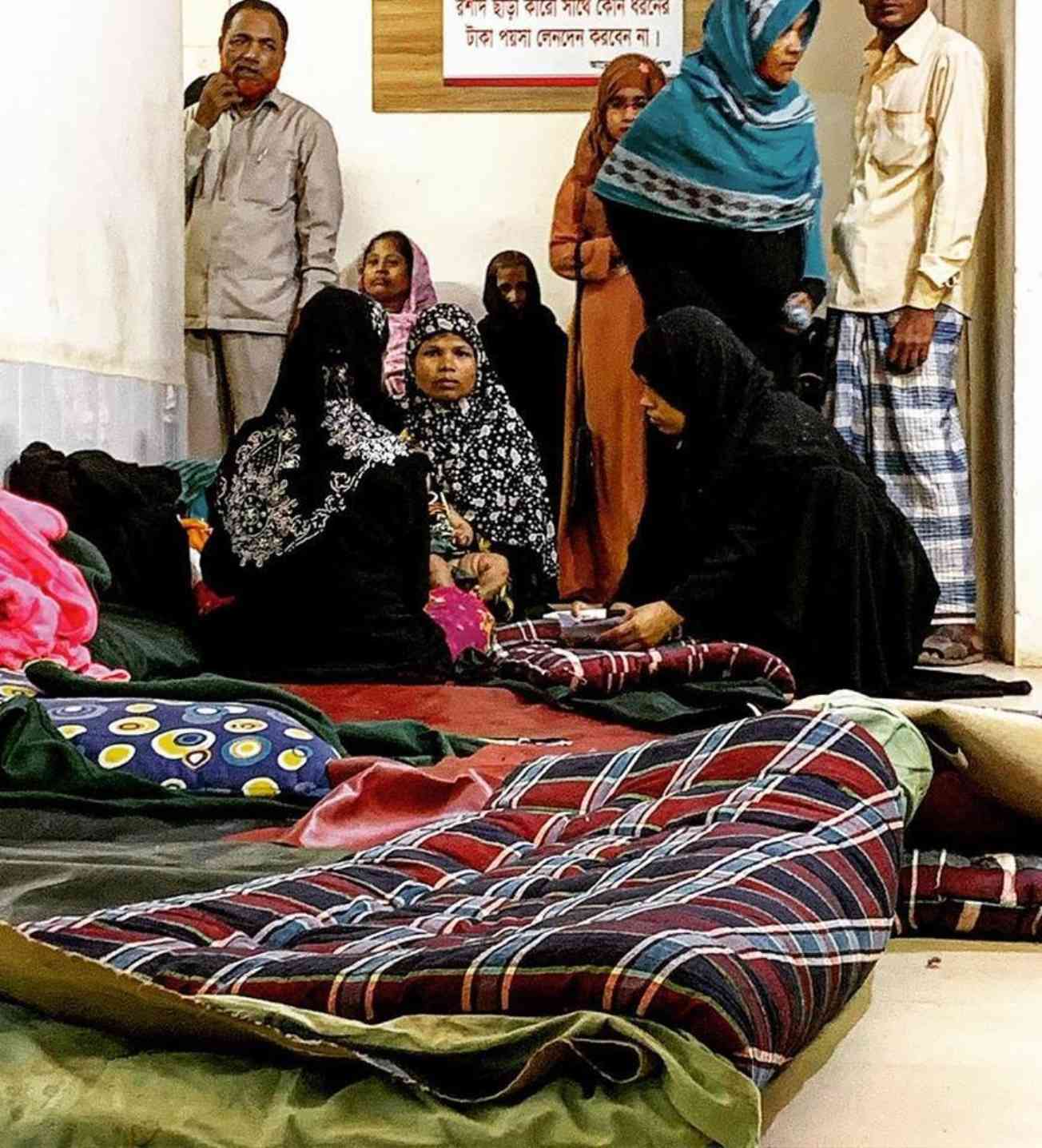

We visited the hospital on Tuesday: surgery day. Mothers and children crowd the halls, but only seven to ten will be the lucky candidates today. Children born with cleft lips and cleft palates lie with their mothers alongside other children with chicken pox or acute watery diarrhoea. No one is stressed, inpatient, angry or insistent. They wait.

Here, Their Story is Our Story (TSOS) Director of Photography, Christophe Mortier captures one of the "lucky" ones as they are being assessed by the hospital staff.

You can help give hope to more refugee children

Sixty Rohingya children are born a day in Cox’s Bazar refugee settlement. The birthrate of children with cleft lips and cleft palates is high, and yet only seven to ten of those children win the luck of the draw to get their cleft repaired.

And then, of course, there are children whose lives are at immediate risk: the children with acute watery diarrhoea, due to unsanitary living conditions, and severe acute malnutrition, and those at risk of diphtheria, measles, respiratory problems and skin diseases.

The staff at HOPE Hospital for Women are doing what they can, but the hospital desperately needs funds to prevent more unnecessary death and disability to this vulnerable community.

The Rohingya children have seen more tragedy and experienced more trauma than you and I could probably stomach watching on a cinema or television screen. Make a difference to their lives by donating to HOPE Hospital for Women, so that they look forward to the next part of their story with better health and some hope.

Tomorrow, we will sharing an exclusive video from on the ground in Cox’s Bazar for International Women’s Day. Read yesterday’s story from Bangladesh: The ‘lost’ generation of Rohingya children.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Share refugee stories online and in life amongst your friends and colleagues to help challenge misconceptions and misunderstandings about refugees.

Donate to Their Story is Our Story (TSOS) so that we can continue sharing refugees’ personal stories.

Donate to Hope Foundation for Women and Children of Bangladesh so that Hope Field Hospital for Women can continue to provide a safe haven for women and children inside the Refugee Camps.

Get involved with HumaniTerra by donating funds or volunteering to work on the ground to help rebuild the care system in a sustainable way.

Author: Emma Nobes

Image credits: Melissa Dalton-Bradford and Christophe Mortier (final image)

Official Statement on the Detention of Refugees and Ongoing Community Violence

With another death in Minnesota and continued violence toward individuals and groups standing up for their communities, we acknowledge the profound fear and uncertainty people are feeling--not just locally, but across the country.

On top of this, there are reports that refugees invited and admitted to our country through the U.S. Refugee Admission Program are now being detained, meaning that our new friends and neighbors feel that fear most acutely.

Refugees have already fled violence and persecution once. They came here legally, seeking safety. In moments like these, we reaffirm our commitment to building communities where refugees and immigrants can live without fear. Where they can go to work, send their children to school, and build lives of dignity and belonging.

We call for due process, accountability, and humanity in all immigration enforcement operations. We call upon our leaders to demand the demilitarization of our neighborhoods and cities. And we call on all of us to continue the work of welcoming and protecting those who have been forcibly displaced from their homes.